Just outside St. Louis, in the inner-ring suburb of University City, there’s a little neighborhood often called the region’s unofficial Chinatown. Growing up in the area, it was one of my favorite places to be; reflective of the city’s diversity and vitality, it opened up the world to me. This past December, when I went home for the holidays, I discovered that what was once a beloved strip of immigrant- and minority-owned businesses there — a Korean grocery, a pho shop, a Jamaican joint with vegetarian options, a Black-owned barber shop — had been bulldozed and replaced by a double-lane drive-through Chick-fil-A.

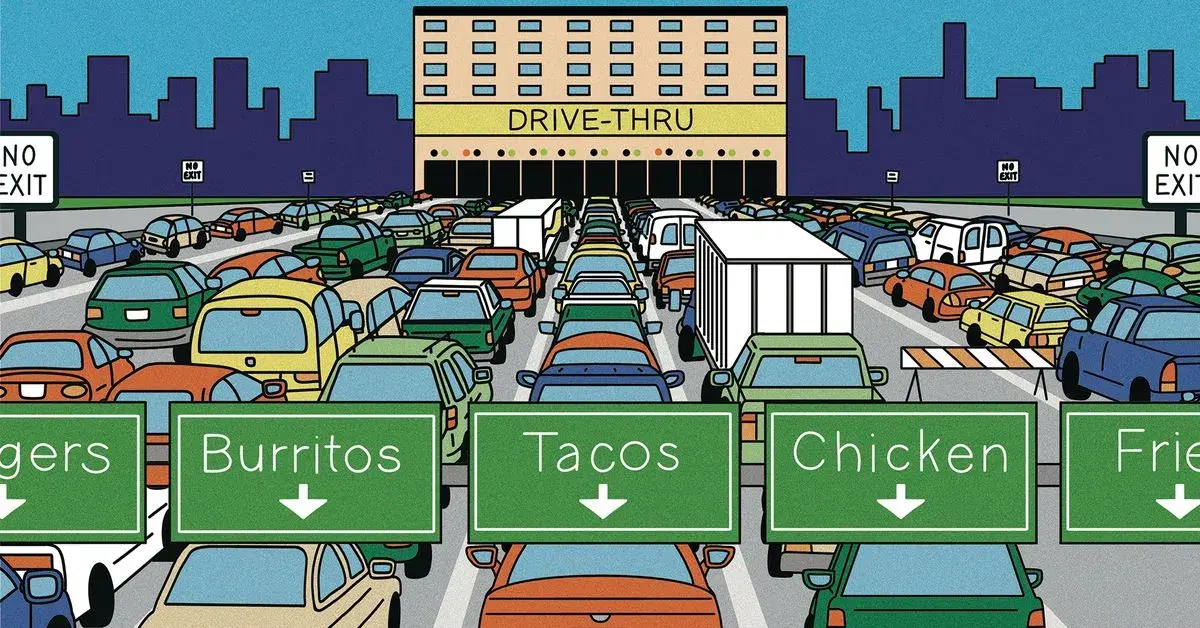

“Drive-throughs have been around a long time,” Charles Marohn, a former traffic engineer and well-known critic of America’s car-dependent urban planning, told me. Today, he said, “they’re becoming bigger and more obnoxious.”

That trend conflicts with a key objective that US cities are increasingly prioritizing: creating a safer, cleaner, walkable, livable urban environment that’s less dependent on cars. St. Louis and its suburbs, for example, in recent years have been building out bike lanes and walking and biking paths, including a segment that runs right up to the site of the new fried chicken and Chipotle drive-throughs. Where, exactly, are the people walking or biking that path supposed to go when they arrive at a development designed to be navigated only by car?

This was a really good article that I wanted to share.

🤖 I’m a bot that provides automatic summaries for articles:

Click here to see the summary

That trend conflicts with a key objective that US cities are increasingly prioritizing: creating a safer, cleaner, walkable, livable urban environment that’s less dependent on cars.

Some brands that have long offered traditional drive-throughs, like Chick-fil-A and Taco Bell, are adding dedicated lanes for mobile orders made in advance — part of what’s causing mega drive-throughification.

The more fundamental problem, as Minicozzi sees it, is the system that allows and even encourages developers and big business to waste so much precious land on economically unproductive sprawl, ultimately forcing the public to pay for it in the form of road maintenance.

Americans spend much of their days traversing non-places — settings for the movement and storage of cars rather than for humans to linger — making social connection “exhaustingly difficult,” as Muizz Akhtar put it in Vox, and contributing to our loneliness epidemic.

“A good part of any day in Los Angeles is spent driving, alone, through streets devoid of meaning to the driver,” Joan Didion wrote in 1989 of the consistently temperate region that somehow represents the apotheosis of car dependence and drive-throughs.

But big city restrictions may not end up mattering much, Klein told me, because the fast food industry sees its future in regions that are friendlier to the drive-through style of development.

Saved 91% of original text.